Cancer in a Nut

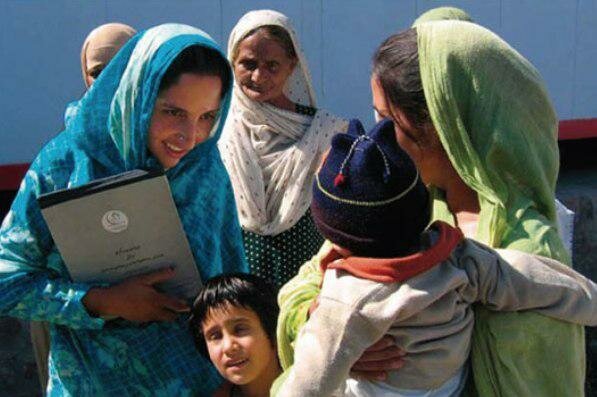

The betel nut is causing rates of oral cancer to rocket in the Indian subcontinent, with children as young as four its biggest users.

Every other day after school, 11-year-old Zohra Ahmed stops by a paan (betel leaf) shop and picks up a packet or two of sweetened betel nuts, or chaalia, as they are known in the Pakistani city of Karachi.

The two tiny plastic packets cost only Rs1 (about US$0.01), and Zohra, whose father is a manual labourer, can afford few other treats. Sometimes the paan seller, who wraps up the glossy, heart-shaped betel leaves with various ingredients to sell to his customers, hands over a few packets of chaalia for free to Zohra and her friends.

“I love the flavour and keeping a piece in my mouth seems to help me sleep,” Zohra told IRIN.

She is not aware that the substance may, according to a growing body of research, be addictive and could result in mouth cancer. Medical experts say the incidence of oral cancer is 2-4% in Europe but as high as 40% in the Indo-Pakistani sub-continent, due to the use of betel nuts, betel leaves and related products.

A fungus released by the betel nuts is known to contain a toxin that doctors believe give rise to cancer.

“I have seen children as young as 12 years with cancerous mouth sores. Others suffer problems which make it hard for them to open their mouths fully. Dentists can pick up these problems early, but visits to dentists are rare here,” said Shahid Akram, a family medical practitioner who works at a charitable clinic in a low-income area of Karachi.

A 2009 study found that while 96% of the 370 children between the ages of 10 and 16 years surveyed were aware of the harmful effects of chaalia, its use remained widespread due to the low cost of the product, a liking for its taste and social acceptability. Children as young as four were known to consume betel products.

“I love to suck on a piece of chaalia or hold it under my tongue,” Asif Pervaiz, 8, said. His father, Muhammad Din, a carpenter, said he was aware of the harmful effects of betel products, but could not persuade his son to stop using them, despite forbidding him from doing so, as “they are so easily available and so many children use them all the time”.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the use of smokeless tobacco is a culturally acceptable habit in Pakistan. Studies from Karachi have shown that 21% of men and 12% of women use betel nut.

For both men and women, the use of betel and chewing tobacco is 20% and 17%, respectively. In medical students, the rate of use was reported as 6.4%, while among primary-school children, the use of areca and betel was 74% and 35%, respectively.

WHO noted the rate of oral cancer in Pakistan is higher than in other countries in its Eastern Mediterranean region and is more prevalent among certain communities.

“Certain groups use betel more often than others, due to cultural factors,” Akram said. “Early diagnosis is the key to successful treatment, but since access to medical care is limited amongst poorer communities, the cancer is often not detected till it is too late and the cancer has spread.”

Among primary-school children, the use of areca and betel was 74% and 35%, respectively.

Chaalia also poses other risks: accidental inhalation of the small nut by children is common, according to media reports and poses a risk of death.

“The government needs to create more knowledge about the risks of betel. The nuts must not be sold to children. I have seen mouth cancer cases and the end stages are extremely unpleasant,” Din said.

This article was first published in IRIN in May 2011.