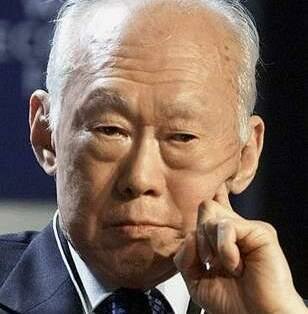

Exit Lee Kuan Yew

The equation Lee Kuan Yew = PAP = Singapore had scrolled across the collective consciousness for nearly half a century.

One of the greatest surprises of Singapore's 2011 general elections was the people’s unequivocal rejection of the People's Action Party style of government. But none could have imagined that the biggest casualty would be Lee Kuan Yew, one of the founders of the PAP, Singapore’s first prime minister and subsequently, de facto Chief despite holding only an advisory role as Minister Mentor.

Indeed, the nations’ shock on 14 May, just a week after the election, at the resignation of MM from the cabinet (together with Mr Goh Chok Tong, Senior Minister) could only be described as seismic in the Singapore political landscape. It reflected the uniquely powerful position of the father of modern Singapore, presumably the only political leader in the world whose name was synonymous with the party he founded, whose name, in turn, was synonymous with the country it rules. The equation Lee Kuan Yew = PAP = Singapore had scrolled across the collective consciousness of the society for nearly half a century.

He was once compared to the immense banyan tree in whose shade only puny little saplings could grow. He was once the mighty Colossus in whose shadow little people cowered.

Was. Had scrolled. Once. Cowered.

It gives one a surreal feeling to write about Lee Kuan Yew’s influence in the past tense. But that is exactly how it is going to be from now onwards, judging from the various public statements made by the prime minister, MM himself, Mr Goh and other PAP leaders, following the announcement of the resignation. Almost in one voice, they spoke about the need for the party to move on, to respond to the needs and aspirations of the people, so painfully made clear to them in GE 2011. The courteous, deferential tone called for by the occasion masked the urgency of the message: the prime minister must be free to act on his own without any interference from the overpowering MM who is also his father.

Perhaps the announcement of MM’s exit should not have been so unexpected, as it had been preceded by a clear harbinger. For midway through the campaigning, when the PAP had already sensed an impending loss of the Aljunied GRC whom earlier MM had offended with his ‘live and repent’ threat, PM had hurriedly called a press interview in which he gently, but firmly, dissociated himself from MM, and assured the people that he was the one in charge. The necessary follow-up action for this public repudiation had obviously been part of the promised post-election ‘soul-searching’, which must have concluded that indeed MM must go.

Despite MM’s assertion, in the joint statement with Mr Goh, that the resignation was voluntary, in order ‘to give PM and his team the room to break from the past,’ doubts about his willingness will be around for a while. For right through the election campaigning he was in upbeat mood, declaring his fitness at age 87, his readiness to serve the people for another 5 years, and roundly scolding the younger generation for forgetting where they came from. Moreover, he had, amidst the gloom of the PAP campaign, confidently stated that the loss of the one Aljunied GRC would be no big deal, and contended, a day after the election, that his blunt, controversial remarks about the Malay-Muslim community, had not really affected the votes. In short, he was expecting to stay on, his accustomed ways of dealing with people, unchanged.

And then came the shock announcement of his resignation from the cabinet, and an uncharacteristic affirmation of the need for change.

That Lee Kuan Yew was prepared to do a drastic about-turn, so at odds with a lifetime’s habit of acting on his convictions, must have been due to one of two causes—either he had been driven into a corner and simply had no choice, or he had a genuine commitment to the well-being of the society, that was above self-interest. In either case, the decision to go into the obscurity of virtual retirement after decades of high political visibility both at home and abroad, must have been most wrenching.

The extent of the personal sacrifice can be gauged by the single fact that politics was his one overriding, exclusive passion upon which he had brought to bear all his special resources of intellect, temperament and personality. He had made himself the ultimate conviction politician with an unrelentingly logical and rationalistic approach to dealing with problems, dismissing all that stood in its way, especially sentiment and emotion. He had developed a purely quantitative paradigm where the only things that mattered were those that were measurable, calculable, easily reduced to digits and hardware, whether they had to do with getting Singaporeans to have fewer or more babies, getting people to keep the streets litter-free, getting children in school to learn the mother tongue. It prescribed a mode of governance that relied heavily on the use of the stick.

The supreme irony of Lee Kuan Yew’s political demise was that the paradigm which had resulted in his most spectacular achievements as a leader taking his tiny resource-scarce country into the ranks of the world’s most successful economies, was the very one that caused his downfall. The related irony of course was that a man of admirable sharpness of mind, keenness of foresight and strength of purpose had failed to understand, until it was too late, the irrelevance of this paradigm to a new generation of better-educated, more exposed and sophisticated Singaporeans.

There is no simple explanation for such a paradoxical disconnect between a man’s massive intellectual powers on the one hand and his poor understanding of reality, on the other (complacency perhaps? political blindsight? political sclerosis?) A detailed analysis of the irony, substantiated with examples over more than four decades of Lee Kuan Yew’s leadership of Singapore will be instructive for understanding this unique personage.

Even a cursory review of the history of Singapore will show that it was Lee’s actions, driven by the passion of his convictions, that had saved the nation, at various stages in its struggle for survival in a volatile, unpredictable, often unfriendly world. With his characteristic strongman’s ruthlessness, he cleaned up the mess caused by Communists, communalists, unruly trade unionists, defiant students and secret society gangsters plaguing the young Singapore. Within a generation, he had created an environment where Singaporeans could live safely, earn a living, live in government-subsidised flats with modern sanitation. Ever conscious of Singapore’s vulnerability, he was ever on the alert to smack down its enemies and, even more importantly, to seize opportunities to raise its standard of living.