One Less Bad Guy in the World

Americans may rejoice over the death of Osama Bin Laden, but surely, the war against terror isn’t yet over.

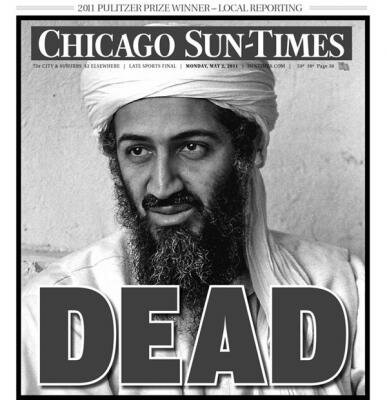

On May 2, much of the Twitterverse – and the free world – went abuzz and agog over the apparent death of Osama Bin Laden. There was a somewhat glowing tinge of triumph, that the death of Osama meant a new dawn, a milestone, a very important moment that the “free world” (emphasis on the quotes) should celebrate.

There’s one less bad guy in the world, as the author Nicholas Sparks wrote on his Twitter account. We can now be free from the clutches of a man who, in many ways, had the single most murderous and twisted interpretation and implementation of a sick and sadistic ideology that he can rightfully claim to be his own. The war is over… or so we think.

There’s celebration in Washington, as there is co-celebration here in Manila. It may “matter less” here, yet our familiarity with the pain and toll of terrorism should justify a reaction from these shores. But there’s something unsettling about rejoicing about the death of enemies or even terrorists: not the earnest self-reflection that comes with the reality that Osama’s death isn’t “victory”, but a cold, hard reality of a protracted war.

The United States can learn a lot from us here in the Philippines.

Not that terrorists shouldn’t die in a War on Terror – this is, after all, a global purge against them – but it somehow reinforces the idea of “one man’s terrorist is another’s freedom fighter”. There’s a sort of obvious juxtaposition: those who dance because Osama died do so at the expense of his supporters, who mourn for the death of an ideologue. And the seeds of terrorism often grow from the nourishment brought on by emotions.

For all its military might, the United States can learn a lot from us here in the Philippines. We’ve killed many terrorists of many different sorts in these islands: international terrorists, community terrorists, so-called terrorists. Yet there was never a feeling of closure when a terrorist passes on, for terror – and the ideology that perpetuates terror – outlives guns, bombs, and terrorists. Sure, there’s one less bad guy in the world, but that never meant having one less bad idea.

The death of a terrorist in the Philippines didn’t mean an end to the crossfire in the jungles, the grenades thrown at schools, and the bombs that detonate in buses.

Not being an American, I could probably not understand the deeply personal feelings that run through the current of some sectors of American society with the death of Bin Laden. I do in fact, but that feeling is tempered by my own experiences in my own country, where high-profile terrorists are killed more frequently than in the United States. The death of a terrorist in the Philippines didn’t mean an end to the crossfire in the jungles, the grenades thrown at schools, and the bombs that detonate in buses.

Too many times, the death of one or two terrorists meant a beginning of new waves of terrorism. It didn’t make me feel any safer, because terror lives and thrives in forces bigger than the men who spread it. And it’s true in other countries: Afghanistan, Iraq, and perhaps even the United States. Terrorism outlives the terrorist, which makes it such a potent weapon of fear and destabilisation.

The thousands of American lives lost in a decade-long War on Terror were lost looking for a fugitive. The United States government and its allies spent billions of dollars in a mission that took ten years and two Presidential terms to complete. The war may be consummated, but it was never commensurated. It’s a step to kill Bin Laden, but it’s certainly not the finishing line. While personal feelings of joy and bliss from the death of the deadliest terrorist of the 21st century should not be extinguished immediately by cold hard doses of politics, it should nonetheless be tempered by the fact that justice is more than just the killing of one bad guy. The war may have just begun. That we who are all the willing to do it should rejoice today, but even that joy should be tempered by the cold, hard realities of war: the cost of arms, the cost of deployment, the cost of lives.

The world may be safe from the pontifications and threats of Osama through tapes and videos, but not from terrorism yet. There is something morbid in rejoicing the death of an extremist thug, especially when it is not framed by the fact that the free world lost tens of thousands of lives in the pursuit of someone labelled short of Evil Incarnate. Or morbid, knowing that every misguided step in the dance to praise the killing of Bin Laden is another step in teaching a man to take his helm. Or morbid, knowing that peace is not assured by killing a man.

The killing of one bad guy may not be justice, but the killing of extremist ideologies that make those bad guys would be a step in the right direction, in my view. Lifting the remote parts of the Middle East from abject poverty and isolation may mean less of the terrorist cells, and more people can have the kind of education and opportunities needed to expand one’s world view besides from that taught by the extremist “mullah” in a faraway “madrassah”. Killing these bad ideas may not be taken lightly, but at least the clash of ideas of what civilisation is, is fought in the realm of the intellect, and not with guns and tanks.

Perhaps the best way to liberate those who do not represent what we believe in or subscribe to beliefs that threaten our own way of living is to teach them, to develop them, and to enable them to seek out the opportunities that we enjoy in this part of the globe on their own terms. Perhaps the War on Terror is a duel of the minds, not an exchange of gunfire. Perhaps the way to realising genuine peace is to do so peacefully, and not for soldiers and warriors to shed blood. Not in conflagration, but in education, irrigation, and cooperation.

Osama Bin Laden never properly represented Islam, but he was a charismatic thug, a criminal, a thug hiding under the guise of religion. In a way, Osama thrived on war, and was the bad guy we have one less of in this world. Indeed, we should be happy for it. Yet to have less of the likes of him, we don’t simply kill the guys: we kill the idea. We’re a step closer, but the war is far from being Mission Accomplished.

This post was originally published on The Marocharim Experiment in May 2011.