Power to the People?

As winter power shortages shroud Nepal in familiar darkness, the country’s hydro debate grows more thunderous.

With winter in full swing, the spectre of planned power cuts, euphemistically called “load shedding”, is haunting Nepal's electricity consumers. The country’s citizens dread this time of the year, which not only brings the Himalayan chill but also the inevitable power shortages, beginning in October or November and continuing until the monsoon arrives in June or July. By February the cuts are expected to intensify to 16 hours a day.

It’s a pattern that is fuelling the country’s debate over hydroelectricity and the frustration over stalled dam projects. With a government eager to build large-scale schemes pitted against an active civil society keener on small-scale hydropower, progress has trickled to a stop. And a middle way is needed fast.

The situation in Nepal was not supposed to be like this, or so its people were led to believe. Almost all educated Nepalis know the officially stated figures: the country’s 6,000 rivers (many of them snow-fed) are supposed to be capable of generating 83,000 megawatts. But Nepal only manages a meagre 698 megawatts of hydropower – far below demand – so such a high estimate is increasingly questioned.

At a recent seminar on improving the Nepal Electricity Authority – a government body that buys, monitors and supplies electricity in Nepal – the energy minister, Dr Prakash Sharan Mahat, sounded cautious but optimistic. Reminding the audience of the ministry’s goal to produce 10,000 megawatts in 10 years, he said: “We’ll have to wait for four to five years, then we don’t have to face load shedding.” When a participant questioned the usefulness of a seminar conducted in a luxury hotel, he replied, “We should think big.”

To think big or small is at the heart of the hydro debate in Nepal, a country rich in biodiversity but also endowed with fast flowing rivers that surge through the Himalayas.

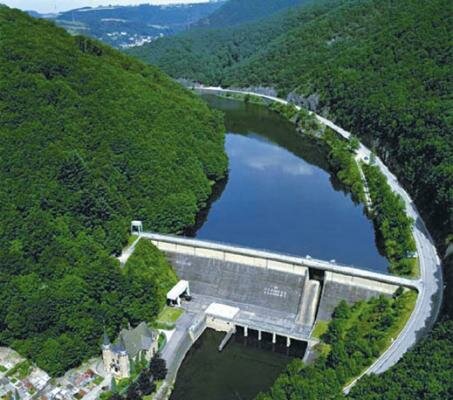

To think big or small is at the heart of the hydro debate in Nepal, a country rich in biodiversity but also endowed with fast flowing rivers that surge through the Himalayas. The coalition government, like its predecessor, the Maoist government, has promised to cash in on the nation’s “liquid gold”. Though most of Nepal’s hydroelectric power can be generated using run-of-the-river systems, large dams, some argue, are inevitable for a nation only just emerging from the shadow of a decade-long civil war and desperate for development and growth. Government policy therefore remains large-scale and export-oriented.

But Nepal’s “big thinking hydrology” has seen strong opposition from a vibrant civil society, especially since the restoration of democracy in 1990. Indeed, Nepal’s quest to exploit hydropower potential mirrors the political upheaval of the past two decades.

The early 1990s marked the World Bank’s infamous withdrawal from the 404-megawatt Arun III project located on the eponymous river in north-eastern Nepal. On the basis of a petition filed by members of the local community and activists, Nepal’s Supreme Court ruled that the World Bank and Nepalese government must provide information on the project to the public. There were several criticisms of the scheme, including the fear of a rise in the electricity tariff (the project’s estimated cost was US$5,400 per kilowatt), the ecological impact of the plant on the rich biodiversity of the Arun Valley and the claim the project was too big for Nepal (the cost was equal to the country’s entire annual budget).

These concerns eventually forced the World Bank to back out, an event often blamed for shattering the dream of a prosperous Nepal. Writing a decade later in his book “In Defence of Democracy: Dynamics and Faultlines of Nepal's Political Economy”, former finance minister Dr Ram Sharan Mahat rues the project’s demise: “Arun III was lost, and with it the attractive financial package whose benefits included the huge social profit potential to boost the national revenue also vanished.”

The Mahakali Treaty between Nepal and India was signed in the mid-1990s. It dealt with the proposed 315-metre , multipurpose Pancheshwar dam, with storage capacity of 12.3 billion cubic metres and a 6,480 megawatt power house.

Nepal’s Supreme Court determined that the treaty required ratification by a two-third majority of the parliament. After intense debate, the agreement was finally ratified on November 27, 1996, but deep disagreement split the main opposition party (the United Marxist Leninists).