I spent almost seven years of my life in Shanghai. Being Russian, I was always told by locals that there once was a large Russian community in the city in the 1920s and ’30s. They would say: “Oh, you’re Russian! There were a lot of people from your country here, I can show you where they lived. They were called White Russians, because their skin was white. They’re all gone now.”

Hearing this piece of information felt strange, especially since very few Shanghainese could add anything else to it. As I realised later, most of the locals had a very vague understanding of why the Russians were here, and who they were. Speculations about the meaning of “white” were quite amusing too.

It’s not as if the history of the Russian community in Shanghai has never been studied. Russian and Chinese historians have written several books, and former members of the Russian community in Shanghai have published a number of autobiographies. It’s not a secret or an insignificant subject.

Evidently, for most of today’s Shanghainese, the history of the Russian community is merely a long-gone part of the colonial past that is too bitter to remember and is thus forgotten.

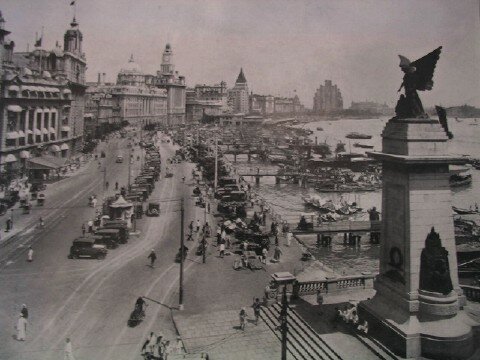

Shanghai Bund

Russian emigration in general is surrounded by an aura of romance and honour. Unlike people moving to the New World in order to seek their fortunes, most of the Russian emigrés fled the country to save their lives after the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917. The entire social elite and most of the middle class became fugitives, leaving behind their homes, their possessions, and their entire lives.

Few of them were keen adventurers and all of them missed their homes. Left with nothing, they had to start over from scratch, and their lives were filled with dramatic events. Yet to the very last moment, they held on to the hope of returning to their native land, until, many years later, the hope faded into nothing, leaving their offspring to settle down around the globe without so much as a distant memory of their Russian roots.

The latest research shows that there were about five million Russian emigrés scattered around the world. This was probably the biggest exodus from one single country in the history of humanity. Most of the Russian aristocrats and rich people from the West of the country settled in Europe; but thousands and thousands of people from the Russian East fled through Vladivostok to China and landed in Manchuria, Harbin, Dalian, Tianjin, and Shanghai. Many of the latter were families from the middle class and from the White Army.

The White Army was the military arm of the White Movement that comprised some of the Russian forces, both political and military, which opposed the Bolsheviks after the October Revolution. The White Movement and the White Army generally (although not always) supported private ownership and the monarchy. During the Russian Civil War from 1918 to 1921, they fought against the Red Army that supported the Bolsheviks and communism. The members of the White Movement were known as White Russians. This is where the name for the Russian emigrés came from—not, as my Chinese friends suppose, from the pale colour of their skin!

Through many years of foreign colonisation of China, Shanghai had been very cosmopolitan. Foreign concessions around Shanghai harboured thousands of Europeans and Americans. However, until 1917, when the October Revolution blazed up, the number of Russians living in Shanghai never exceeded 500. They were mostly merchants and employees of the Russian consulate that was established in 1860.

Slowly, Shanghai became the centre of Russian interests in the region. In 1896, the Sino-Russian bank opened its branch in Shanghai. It was to become the most influential Russian economic institution in the city. The Sino-Russian bank was created by the Russian government to finance construction of the China Far East Railway. It was one of the largest financial organisations in the Far East. In 1926 the bank’s assets were transferred to the Soviet government; but the bank building is still there, on the famous Shanghai Bund.

White Hot Explosion

After 1917, the number of Russians in Shanghai grew drastically. No one noticed how the Russian population there was increasing until December 1922, when the fugitive White Army naval fleet, led by Admiral Yury Stark, arrived at the estuary of the Yangtze River. After this event, the Russian population of Shanghai reached 6,000.

These fugitives had made their way from Vladivostok after long weeks of suffering and hardship on ships that were not really designed to carry passengers. However, the Shanghai administration refused to allow the refugees to leave the vessels. According to one of the witnesses, the ships stayed in the Shanghai harbour for a long time before thousands of their passengers—legally and illegally—found their way to shore.

Their lives in Shanghai were very tough at first, but being honourable people with good education and proper upbringing, Russian emigrés preferred an honest living. During the years from 1923 to 1925, almost none of the crimes that involved Russians in China were registered in Shanghai.

Desperate for cash, these emigrés undertook jobs that no other Europeans would accept. There were Russian porters, Russian handy men, Russian construction workers—doing jobs that in those days only poor Chinese would do. Women worked as teachers, nannies, maids, movie ushers and dancing girls. Their lives were quite different from what they were used to back home. However, no matter how bad things were, Russians worked hard and soon, having saved some money, they started to open their own businesses and many became quite successful.

Perhaps not surprisingly then, Russians managed to get along with Chinese better than anyone else in the foreign community. They had a lot in common and not only co-existed peacefully with the Chinese population, but also actively cooperated with it.

In 1924, China established diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union. From that day on, the Russian community in Shanghai started to grow quickly, as Russian emigrés from Harbin were moving down south.

Ecola Municipale Remi circa 1942

During that period, foreign concessions were states within a state, with their own rules, laws, administration and police, that recruited foreigners only. Eventually, the remaining members of a group of White Army Cossacks—under the command of General Fedor Lvovich Glebov—became the core of the Russian volunteer brigade that was created to protect the international concessions from the approaching KMT army of General Chiang Kai-shek. Russians were good soldiers and many served in police units protecting international settlements. Russians were quite popular, especially after many of them learned English and Chinese.

By the mid-’20s, the situation of the Russian emigrés had improved considerably. Many of them began to move into the French Concession. There, on its main road that used to be called Avenue Joffre (now known as Huaihai Zhong Road), Russians opened dozens of shops, restaurants, and grocery stores. Quickly the number of Russian residents there grew to four times the French population. Soon, the “French Concession” became know as “the Russian Concession”—among both foreigners and Chinese.

According to estimates, by 1936 there were around 30,000 Russians in Shanghai. As the question of personal survival was solved, Russians began to take care of preservation and development of Russian culture and education. The 1930s came to be regarded as golden times for bustling Shanghai and as the peak of Russian cultural life in the city.

In no time, Russian migrants built two orthodox churches in the French concession, opened a theatre and a ballet school, and established a symphonic orchestra that was considered the best in the Far East. Russians printed their own newspapers and magazines.

> TO White flight from Red Russia (Part 2 of 2)

Comment on this post

HOUSE BLOGS

From Jerusalem to the West Bank

DAN-CHYI CHUA

Talking the Walk

DEBBY NG

Words and Letters

CLARISSA TAN

Chilli Padi

VIVIENNE KHOO

FOLLOW US

Maria Maximova

Maria Maximova

%2005411%20My%20Dog%20ll.thumbnail.jpg)