BROWSE COUNTRIES/ TERRITORIES

The Chinese-Arab connection

As the political tensions strangle the livelihoods of ordinary Palestinians, the traders are seeking new avenues to make a living from the Middle to the Far East.

“Zhe li xian zai lao wai bi ben di ren duo,” commented Fatid in fluent Mandarin, as we walked through the Old City of Hebron. There were now more foreigners than locals in this part of town, he said, referring to the presence of international aid workers and volunteers in the city. “Laowai”. He had used the mainland Chinese slang for foreigners.

Fatid is a Palestinian, born and bred in Hebron. Now a young man in his late twenties, he lives in China, specifically in the city of Yiwu, near Shanghai, where he had been for five years now. Fatid was on a two-week vacation back home to see the family. In less than a week, he would be back in Yiwu.

“Chong zhe li dao Dubai dao Shanghai,” he explained.

The Middle East – Dubai – Shanghai route he described had over the eight years brought hundreds of thousands of Arab traders to China. From Shanghai, it was a mere four hours to Yiwu's wholesale markets, where like Fatid, they would ply for cheap Chinese-made merchandise which they then export home.

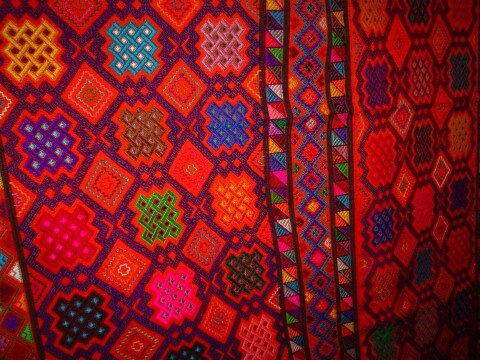

Fatid and I walked past a souvenir shop. Pointing to a woven scarf hung outside a shop, he said, “Zhe shi zhong guo lai de, ke shi ta men shuo shi zhe li de.” The scarf is Chinese-made, but they will sell it as locally-made.

In the exotic Middle-eastern bazaars, China-made clothing and plastic kettles, are now as common as the traditional tapestries, shisha water pipes and old-style Arabic coffee pots. While tourists examine local handcrafts in Cairo's main market, it is the electronics stores that attract the locals, looking at the array of Chinese-made shortwave radios.

I asked Fatid how he liked living in China, if it was a strange experience for him. No, Chinese people are very good, very kind, he replied.

Yes, they were exceedingly good and kind to the Arabs. After the September 11th attacks, security concerns meant that Arabs were finding it harder to get visas to the US and to a lesser extent the European Union. Around that time Beijing opened its doors to the Middle Eastern countries.

For an Egyptian, it could take him more than two weeks to get an American visa. The Chinese one was issue in less than 24 hours. When it became easier to go to China instead of the West, Yiwu was where the Arab traders headed.

In fact, China had just in April opened a new visa office in Ramallah in the West Bank, complete with its own red round Chinese lantern. There was a demand, according to the Chinese. Last year alone, more than 3,000 Palestinians applied for to go for a Chinese visa.

“The new visa office can facilitate the local visa applicants and promote our work efficiency,” said Yang Weiguo, the head of the Office of China in the Palestinian territories.

“Also, it's a window to show China's image," he added

Fatid pointed out a few shuttered shops which he said belonged to his extended family. They had closed it because there was hardly any business now in this part of the Old City. The family now tends a toy shop just outside the Old City and a clothing shop in Jordan. He took me to visit his grandfather, who was sitting outside his sundry shop, just a few steps away from the Israeli Army checkpoint that led to the Tomb of Abraham mosque, which in turn was just next to the Jewish Tomb of the Patriarchs.

Fatid's family shop is one of the few still open in Hebron's Old City.

Fatid's grandfather was a friendly man, conversant in Arabic, English and Hebrew. He had picked up English talking to the tourists who used to visit the city on pilgrimage, and Hebrew back when the Jews and Arabs lived harmoniously in this city.

The contrast between the Old City of Hebron and the bustling city of Yiwu was not lost on Fatid. Most of the shops here had shut down due to a lack of business and army closures, and it was the foreign visitors that mainly patronised the ones that remained open. In Yiwu on the other hand, there are 20 markets with more than 300,000 stalls. In the last five years, even the number of Arab restaurants have gone up from four to 20, serving different variations of Middle Eastern fare, from Lebanese to Egyptian to Moroccan.

Several of the Arabs have now settled in Yiwu, either having brought their family over or married a local Chinese girl. Chinese from the country's westernmost-province of Xinjiang have also made the journey cross-country to settle among their Muslim brethren. A mosque was constructed four years ago, here and a second one is being planned in Yiwu's biggest market to allow traders to worship more conveniently.

Chinese Mohammed Abdullah is imam at the Yiwu mosque, and he sees about 7,000 worshippers every week. The locals estimate the local Arab population to be several thousand in this small (by Chinese standards) city of two million. Fatid was very enthusiastic about heading back to China. As Palestinians are not allowed to use Ben-Gurion, the main international airport in Israel, he will have to cross the Allenby bridge to the airport in Amman.

We continued walking and Fatid introduced me to his father tending the toy shop.

“He doesn't speak English,” Fatid joked.

We chatted a while, as Fatid translated, and laughed at how Arabic and Mandarin shared the words for father and mother. “Baba” and “Mama”. These were just two words we had in common, but in the bigger picture, the Chinese and the Arabs did seem to speak the same language. Like thousands of years ago on the Silk Road, it is the language of commerce.

This is the last of a three-part series on the divided of city of Hebron, where Israeli Jews and Palestinian Arabs are living segregated in close quarters to each other, creating a largely tensed situation for both sides in the West Bank. The next posts in From Jerusalem to the West Bank will return next week with more features on the situation on the ground.

< BACK to previous post HEBRON - WHERE THE JEWS AND PALESTINIANS MET AND PARTED WAYS

< BACK to other stories in FROM JERUSALEM TO THE WEST BANK

Login or Register

Dan-Chyi Chua began her writing career with Channel News Asia, a regional cable network, before forsaking broadcast journalism to hit the road for a three-year sabbatical through the Middle East, China, Central America and Cuba. She has now grounded herself as a writer for asia! Magazine.

Dan-Chyi Chua began her writing career with Channel News Asia, a regional cable network, before forsaking broadcast journalism to hit the road for a three-year sabbatical through the Middle East, China, Central America and Cuba. She has now grounded herself as a writer for asia! Magazine.

- Asian Dynasties and History

- Conservation of the Environment

- Definition: Culture

- Economy and Economics

- Food and Recipe

- Geopolitics and Strategic Relations

- Health and Body

- Of Government and Politics

- Religion and Practices

- Social Injustices and Poverty Report

- Society, Class and Division

- Unrest, Conflicts and Wars

Another Point

Another Point From Jerusalem to the West Bank

From Jerusalem to the West Bank

Comments

Post new comment