BROWSE COUNTRIES/ TERRITORIES

Villages jump on the Internet Bus

Some companies are using innovative ways to help people in rural areas get broadband and wireless access.

Villages are the lifeblood of most parts of the developing world but many lack internet access. In Asia, a few companies are making use of wireless technology, microfinancing and government deregulation to help people in rural areas jump on the broadband wagon.

In Sri Lanka, villages now have access to 22 broadband sites, each with three to five personal computers and internet phone lines. This is thanks to EasySeva, founded by Stephen Schmida and Tony Nash.

A whole new world...

“EasySeva is helping bring the universe to our community,” said N. Chaminta, who recently opened a tele-centre at Wennepuwa, about two hours north of Colombo. “The internet is like the universe and now we feel connected to it. We are a part of the world for the first time."

The idea came to Schmida and Nash, who have been friends since college, in 2006. Schmida has a decade of non-profit experience in community development, while Nash directed strategy and marketing in telecommunications for many years.

They formed a business plan and won funding from the U.S. Agency for International Development, which provides economic, development and humanitarian assistance. With partnership from the private sector, they set up EasySeva.

Sustainable Livelihood

At the time, Sri Lanka was recovering from the 2005 tsunami. Emergency aid was flowing into the country. The challenge was to build a sustainable livelihood for the affected people. Nash and Schmida wanted to use these funds to help start up a profitable company that would build a network of self-sustaining small businesses.

“We wanted to change what we saw as the growing prevalence of a donor-dependent culture,” Schmida said.

The two partners studied the market and came up with interesting findings.

Firstly, about a fifth of Sri Lanka’s villagers have relatives overseas. There was thus an untapped need for voice, e-mail and remittance services.

Secondly, there were small manufacturers whose basic communications lines were impeding their growth.

Thirdly, there was a shortage of teachers in the villages so the case for online education was clear. In fact, through a link with Microsoft, online English lessons are now available.

A major challenge was identifying suitable entrepreneurs. “We needed people who understood P&L,” said Nash, referring to corporate profits and losses.

For the provision of a broadband link, EasySeva teamed up with local mobile carrier Dialog Telecom.

This was crucial as Dialog was already operating public mobile services in the villages, typically run by individuals. It was decided that this pool of experienced entrepreneurs would be used as the franchisees.

“Business in a Box”

A student taking an English course

To help with the franchisees’ start-up costs, some form of microfinancing was needed so EasySeva formed a partnership with ORIX Leasing in Sri Lanka.

Also, to help bring down the initial costs, Schmida and Nash came up with an easy set-up method so operators could be up and running quickly, as well as maintain service and operations standards.

This was done with what they call “Business in a Box”. The partners packaged the whole setup, making the process fairly transparent to the franchisee.

The package consists of a PC, networking equipment and software. It also provides linkage to Dialog’s broadband wireless network, training on the systems, operation manuals and – most importantly – quality control and customer service. EasySeva shops are not left on their own after start-up – there are regular visits by quality control managers and constant contact with the franchisees.

Another essential part of EasySeva’s business philosophy is that it aims to be fair to all regardless of religion, ethnicity, language, or gender. Almost a third of its franchisees are women.

Nash and Schmida seemed unconcerned when asked about competition. The Sri Lankan government already runs Nenasela, a public service that is a good source for basic internet access. EasySeva is complementary, as it also provides Voice Over Internet Protocol, which costs villagers a fraction of the price of a conventional phone call. Eventually, EasySeva will have remittance and perhaps insurance services.

The main challenges the partners face are getting microfinance for the franchisees and of course, Sri Lanka’s political instability.

For now, the business is growing rapidly. “Everyday there are lines outside of my shop of people waiting to use the internet,” said Chaminta. “They are not just doing e-mail, but downloading e-books, calling friends abroad and getting government application forms."

Wi-Fi Buses

A bus carrying United Villages’ Wi-Fi equipment

United Villages, another private-sector initiative, has a different approach.

Its founder is Amir Alexander Hasson, who was so inspired by a course he took at the MIT Sloan School of Business on Developmental Entrepreneurship that he came up with the idea of “non real time” internet service. United Villages now operates in various parts of Asia, Africa and Latin America.

United Villages runs a service called DakNet. DakNet recruits and trains village merchants who may be running stores or motorcycle repair shops. As long as they have basic computer skills and are deemed suitable, these merchants are then set up with microfinance, a PC and cordless phones.

The trouble is, these villages lack the communications infrastructure to link them to the Web. DakNet solved the “missing link” to the villages by partnering with the bus companies that ply regular routes to these villages. The buses are installed with Wi-Fi equipment, which pick up and send e-mails, Web searches and voice mail each time they pass by the village merchants’ kiosks.

While the e-mail solution may be obvious, how do the villagers do Web searches “offline”?

Well, a customer enters a search on the browser at the village store, which the bus picks up when it passes by. Then, at the town with the DakNet server and internet connection, the search is carried out through the search engines, the top searches are collected, stripped of its adverts and other unnecessary data, compressed again via the buses as they pass by and sent back to the user. Yes, it is slow and cumbersome, but the alternative was no information at all.

How do you make money from all this? Pre-paid cards. DakNet sells pre-paid cards to the village shops and buses at a discounted price; the vendors then mark them up and make some money out of that. A DakNet pre-paid card costs 50 Indian rupees (about US$1.26), which gives the user a phone number and an e-mail ID. A simple e-mail costs one rupee while attachments cost three.

Drishtree

DakNet and EasySeva appear off to a promising start. Drishtree, on the other hand, has been at it for seven years. It now runs more than 1,000 kiosks in villages throughout India. Drishtree is thus in a powerful position to use the current confluence of wireless technology and other enablers, combine it with their know-how and installed base, and rapidly increase growth.

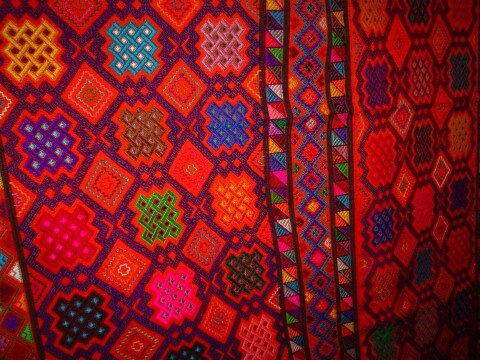

Drishtee now provides microfinance loan applications and processing, insurance services and even an e-marketplace, where village artisans can sell their crafts directly to customers, bypassing the middleman and making better profits.

Some 3 billion people live in rural areas, according to current global estimates. The private sector is showing a way to augment public services by building self-sustaining businesses that can significantly change the lives of villagers. A low-cost setup, local entrepreneurship, microfinance, and using the right technology applications are the crucial factors for success.

At the moment, voice and e-mail services seem to be most sought after. In the near future, remittances, microfinance, insurance, and education will be key. Riding on the advances made in wireless technology and the growth in public-sector services, village entrepreneurship is going places.

Login or Register

Currently a head hunter for the high tech industry, Norman Miranda has spent the last 27 years in various roles all in the IT and Telecommunications industry. He travels whenever time and money allows. Norman continues on his quest to cover every major wine growing region in the world.

Currently a head hunter for the high tech industry, Norman Miranda has spent the last 27 years in various roles all in the IT and Telecommunications industry. He travels whenever time and money allows. Norman continues on his quest to cover every major wine growing region in the world.

- Asian Dynasties and History

- Conservation of the Environment

- Definition: Culture

- Economy and Economics

- Food and Recipe

- Geopolitics and Strategic Relations

- Health and Body

- Of Government and Politics

- Religion and Practices

- Social Injustices and Poverty Report

- Society, Class and Division

- Unrest, Conflicts and Wars

Another Point

Another Point From Jerusalem to the West Bank

From Jerusalem to the West Bank

Comments

Post new comment