BROWSE COUNTRIES/ TERRITORIES

Peace, when?

If you are Lebanese and under 30 years old, you definitely would have lived through war.

Seven. That’s how many times Beirut has been destroyed and rebuilt in its 5,000 years' history. Ask a Lebanese about it, and note the tone that accompanies the reply. Call it defiance. Or resilience. It is a trait that has very much become part of the Lebanese national psyche, and that of the Lebanese artist, Jocelyne Saab.

She is a mere 1.5 metres in height, but exuberant black curls tumble to her shoulders; and dark eyes, piercing and profound with emotion, dominate her small face. Almost 60, Beirut-born Jocelyne spent more than half of her life living in the state of war. As a journalist she covered Lebanon's 1975-90 civil war. This was a period when more than a million Lebanese fled the country.

THE IDEALS

“You want to go out to buy bread; you take risks. You don't know what is going to happen to you.” For Jocelyne it was not only professional duty that made her stay. She saw a paradox in the midst of all that fighting. In the capital that came under siege, she saw meaning in life.

“When you decide to stay and not fly away, you defend an idea. You take a position.” But struggling for ideals in a war is a double-edged sword. “Facing deaths everyday is totally destructive. You are destroyed [in] each revolution. I am excited for having done something good, but it made me sick physically.”

Jocelyne pauses.

“There is something in me that is broken for sure.”

She did eventually walk away from Lebanon. For years after, she was going in and out of hospitals in France for treatment, but as she realised today, the past remains with her.

THE INSTALLATION

Jocelyne now expresses herself through art, and she revisits her homeland in an installation she created called “Strange Games and Bridges”, commissioned by the Singapore National Museum.

After last year's war in Lebanon, she returned to the country, taking pictures of destroyed bridges. Combining them with footage she had filmed from the earlier civil war, she created her installation.

A mechanical hum drones constantly over the exhibit as you enter. It is meant to evoke a sense of raids taking place overhead. An unseen musical box is wound up, and just before the melody comes on, the winding begins again. And again, and again.

This is the accompaniment to a seconds-long footage played and re-played on a white screen. There are three young men, dressed in army fatigues. Their faces are never shown. All one can see are their slight profiles and backs as they swivel nonchalantly on ’70s-style bar stools. One has a Kalashnikov rifle on his lap and a cigar hanging out of his mouth. In the background are grey concrete buildings on an empty street.

The setting, bizarrely enough, was not staged. Jocelyne filmed it in Beirut during the civil war, with another series, that of a bigger group of younger boys.

Barely 11 years old, the boys were on a trip to a beach town for a respite from the fighting in the city. This was a group of children at play.

One boy pretended to be dead as another dragged his small body while glancing side to side for “enemies”. The other boys had made for themselves weapons out of pieces of wood. They knew their roles and they knew how to take cover, from behind one structure to another.

An observation from the artist: “This was 1976 when I shot them. They are probably fighting now.”

War Correspondent turned artist: Former journalist Jocelyne Saab lived through Lebanon's civil war and now preaches a message for peace through her art.

THE LEGACY OF LEBANON

Lebanon is unique in the Middle East in that it has a large Christian population of about 30%. A drive-by shooting at a church triggered the civil war of 1975-90, with militias from both sides carrying out random killings, murdering thousands.

Initially the Muslims—despite being allied with the Palestinians from the 15 refugee camps in the country— were overcome and left displaced in their own territories. But that did not stop them from continuing their battle to try and wrestle political power back from the Christians, the war’s then victors.

It did not take long for Syria to intervene in 1976 to force a ceasefire. Then Israel came into the picture, in southern Lebanon, to buffer itself against attacks by Yasser Arafat's Palestinian Liberation Organisation that was based there. What followed was the seven-week siege of Beirut in 1982, one of the seven times when the capital was devastated.

Beirut's Muslim quarter still bears witness to that siege. Many buildings there remain decrepit, almost a world away from re-built areas like the commercial centre where colonial-era buildings have been extensively and beautifully restored.

The centre of the city near its main plaza, Martyrs' Square, is captivating. Beirut is possibly one of the world's most stunning cities, set against the rippling Mount Lebanon range, as the corniche along the city's northern edge traces the outline of the Mediterranean's sapphire waters.

Yet, Beirut is as haunting as it is beautiful. One of its tallest buildings is the skeleton of the former Holiday Inn perforated by rocket fire. The facade has been blown off so the rooms are left without doors and windows on two sides, left bare for all to see.

All over the capital are churches and mosques in various states of destruction. A walk through the city is a stroll through a war zone.

Being Lebanese doesn't make it any easier for Jocelyne to make sense of her country's turbulent history. “

Is it inherent for men to fight? It is so easy to fuel the war. “

Civilisations: Beirut has been continuously inhabited and is a city built upon layers of history.

A game of backgammon under the Mediterranean's glorious sun

THE WINOGRAD REPORT

In Israel, they could not quite decide if they had fought a “war” against Lebanon. It was a matter of semantics. They were technically battling not a state, but a terrorist group, the Hezbollah, whose fighters had crossed into Israel from Lebanon on July 12, 2006, killing eight soldiers while capturing a further two. The following day, the retaliatory air strikes came and so did the raids and the bombings. That went on for a month before a UN-brokered ceasefire delivered a fragile truce.

There's been no apparent winner in this conflict that the Israeli Knesset finally named the “Second Lebanon War”. (The first being in 1982, which saw Israel occupy southern Lebanon for three years.) In the second war, Lebanese casualties stood around 1,400. In contrast, Israel lost 39 civilians and 119 soldiers.

An official Israeli inquiry into the conflict found the government and Prime Minister Ehud Olmert had recklessly led the country into war without a plan. Olmert was faulted and Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah cheered. "When the enemy entity acts honestly and sincerely, you cannot but respect it."

The Lebanese press barely had time for a final analysis of the Winograd Report when more trouble erupted on the home soil less than a month later, on May 20. Soldiers were fighting the militant group from Fatah-al-Islam holed up in a Palestinian refugee camp near the town of Tripoli, Lebanon's worst internal feuding since its civil war.

One out of every 10 in Lebanon's population of almost four million is a displaced Palestinian. They are foreigners in the country and are not allowed to integrate or work. Instead, they are condemned to festering in the refugee camps over which Lebanon has no jurisdiction under the Cairo Agreement signed in 1969.

The PLO, which was effectively given control of those camps, has abandoned them ever since leader Yasser Arafat found legitimacy over territories within Israel, leaving them to the militias that had been allowed by the same Cairo Agreement to arm themselves for the purpose of fighting Israel.

No Israeli government will let these Palestinian refugees return because their presence will upset the slender Jewish majority in the Holy Land. So this is a people in perpetual limbo, unwanted in Lebanon, or anywhere else.

THE PHOENIX

Thousands of years ago, it was from this strip of land that the cedars were sent to build tombs of pharaohs and the temples of the ancient Jews, where the Phoenician empire was based. Today, the cedar is still a symbol of pride on Lebanon's national flag.

The proverbial phoenix is indestructible. When it is hurt by its enemies, it erupts into flames and from its ashes emerges a new phoenix. Lebanon has definitely burnt. The question is, will Lebanon emerge from its ashes?

Re-building was begun by former Prime Minister Rafik Hariri, and it is impossible to discuss Lebanon without talking about him.

The post-civil war reconstruction of central Beirut was his pet project, into which he poured millions of dollars. But it was what he achieved in death that truly impacted Lebanon.

Since Lebanon sought help from Syria in its civil war, its neighbour had been retaining its influence over Lebanese politics, refusing to leave. When Syrian pressure forced the Lebanese parliament to extend the term of their man in Beirut, President Emile Lahoud, Hariri resigned. Barely three months later on Valentine's Day 2005, Hariri was assassinated in a car explosion. Syrian involvement was immediately suspected.

The death of this outspoken critic of Syrian presence in Lebanon rallied the Lebanese with diverse agendas towards one sole goal: to drive the Syrians out.

Thousands camped out on Martyr's Square, and they remained till Damascus got their message. That took two months. On May 31 this year, the seaside promenade where Hariri was killed was finally reopened. They filled up the seven-metre-deep crater caused by the blast. That same morning, Lebanese woke up to news that the United Nations Security Council had passed a resolution for an international tribunal to try the suspects in Hariri's murder.

Opinion is split on whether that just means more foreign intervention into the country. But Lebanon has always been and will be divided. Its media scene is the most differentiated and vocal in the Middle East, and this reflects the diversity of this highly literate country. There are officially 18 religious sects in the country, and they only comprise the ones recognised by the constitution.

Lebanon's future depends on how well the Lebanese identity can unite these disparate factions.

Lebanon knows the road to peace in the Middle East is always convoluted. It was still under French mandate when her most famous son, poet Khalil Gibran, author of “The Prophet” penned these words:

“In the Middle East there are two processions: One procession is of old people wailing with bent backs, supported with bent canes; they are out of breath though their path is downhill.

“The other is a procession of young men, running as if on winged feet, and jubilant as with musical strings in their throats, surmounting obstacles as if there were magnets drawing them up on the mountainside and magic enchanting their hearts.

“Which are you and in which procession do you move? Ask yourself and meditate in the still of the night; find if you are a slave of yesterday or free for the morrow.”

Lebanon is at a turning point and its moment of truth lies in the horizon.

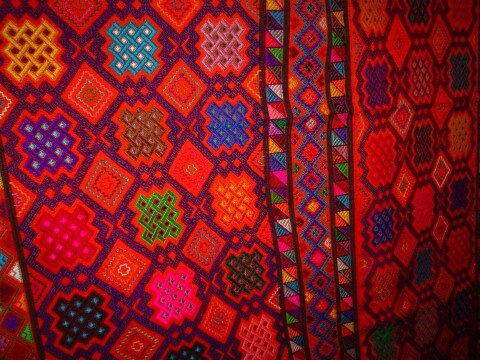

Photos by Jocelyne Saab and Dan-Chyi Chua

Related Story:

Login or Register

Dan-Chyi Chua began her writing career with Channel News Asia, a regional cable network, before forsaking broadcast journalism to hit the road for a three-year sabbatical through the Middle East, China, Central America and Cuba. She has now grounded herself as a writer for asia! Magazine.

Dan-Chyi Chua began her writing career with Channel News Asia, a regional cable network, before forsaking broadcast journalism to hit the road for a three-year sabbatical through the Middle East, China, Central America and Cuba. She has now grounded herself as a writer for asia! Magazine.

- Asian Dynasties and History

- Conservation of the Environment

- Definition: Culture

- Economy and Economics

- Food and Recipe

- Geopolitics and Strategic Relations

- Health and Body

- Of Government and Politics

- Religion and Practices

- Social Injustices and Poverty Report

- Society, Class and Division

- Unrest, Conflicts and Wars

Another Point

Another Point From Jerusalem to the West Bank

From Jerusalem to the West Bank

Comments

Post new comment