BROWSE COUNTRIES/ TERRITORIES

Letters to the President

The rest of the world may consider him a despot or a lunatic, or something in between. For tens of thousands of Iranians though, Mahmoud Ahmedinejad is their salvation.

It is not unusual for motorcades carrying political leaders to be mobbed by the masses, but the crowd had not gathered to catch a glimpse of their president. Rather, many of them had something to say as they waved envelopes in their hands. In each of those envelopes was a letter to the Iranian president, Mahmoud Ahmedinejad; and in each of those letters, a request for help.

This is the premise of the latest documentary by Czech director, Petr Lom. With the consent of the authorities, he interviewed Iranians in different parts of the country about their letters to the president. The middle classes in the cities and university students may scoff at the practice, but it is something many other ordinary Iranians take very seriously.

In the capital Tehran, located in a nondescript building is the Presidential Letter Processing Centre. Here, letters from all over the country arrive and are sorted according to the senders’ gender. (It is “not good for a woman's problems to be read by a man”, explains one of the officials at the centre.) A group of young girls from the student paramilitary, Basiji, read the letters, which are then forwarded to the relevant authorities. No, the president does not answer them personally.

As a sign of the times, there is also a presidential call centre. Iranians are urged by television and radio programmes to call in with their problems. When they do, their calls are recorded into a computer system.

Not all who seek help will get it. In one scene, a bespectacled man is pleading with an official for the approval of a loan. He had been turned down by the banks. After a long conversation, he is left, still without a loan.

Still, people continue to write in with their problems. Everyone knows someone who has written to the president, and someone will know someone else who got a reply. So, they keep hoping and trying. There is a scene in which a middle-aged man runs after a postman collecting the mail for the day. He tries to place a letter into the bag, and an argument ensues over whether he had enclosed it properly in an envelope. At places where the president makes his appearances, though, requests are often hastily scribbled on the spot, along with phone numbers.

“The president works for the people because he is Muslim and has God in his soul. The Jesus you are looking for is in his soul,” says one Iranian.

“Mr Ahmedinejad thinks every letter is a test to get to heaven,” an official explains.

For all his angry, antagonistic rhetoric, Ahmedinejad in person projects a rather pleasant and kind image. He is careful to reach out and touch the arms of the people he talks to, and stops to listen to their problems.

“Letters to the President” portrays a different image of Ahmedinejad. The fact that it was shot with the permission of the Iranian government obviously limited the extent to which the film could have been critical, but its unique storyline makes this an engaging watch. At the very least, the letters and their writers give a rare glimpse into everyday life in Iran, a story that is all too often edged out of the media spotlight by the country's effervescent president.

Director Petr Lom talks about making “Letters to the President”

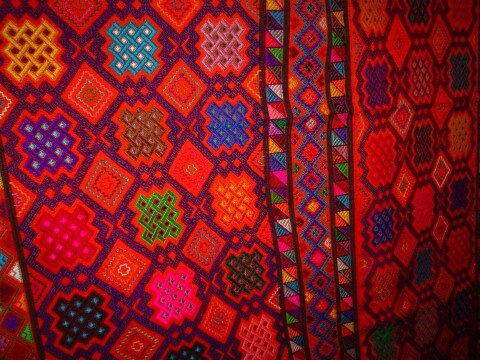

Photo courtesy of Singapore International Film Festival

theasiamag.com: What led to the creation of this film?

Petr Lom: I was interested in Iran for a long time, I have many Iranian friends, and my other work was in Central Asia, not far removed from Iran. Iran is also one of the most important countries in the Middle East, and one that poses the biggest challenges for international foreign policy. When I read that the U.S. might invade Iran three years ago, when there seemed to be serious risk of such a possibility, I thought a film might serve to understand Iran better.

theasiamag.com: How hard was it to be detached from the subject matter, considering the Iranian president is a very divisive and controversial figure?

Petr Lom: Not hard. I used to work as an academic, so of course my job has always been to try to be analytical and impartial. I also strive to make films that respect the intelligence of the audience – and one does that by allowing the audience to think and come to their own conclusions. The imperative for a filmmaker is to be open-minded.

theasiamag.com: How much freedom as a film-maker did you feel you had to give up, in exchange for the assistance of the Iranian government? How did you stay true to your craft?

Petr Lom: I had a lot of freedom in Iran – surprisingly. Of course, there was some self-censorship on my part – I had to honour and respect my hosts – if I wanted to be successful with my film, to complete it – as certainly there was a lot of oversight of my project. I had to make a film that would begin with positive assumptions about the Iranian regime. And I did that. A documentary film is about telling the truth. The truth will come out regardless of any controls/oversight by any authority, anywhere. And you can see that in my film.

theasiamag.com: How was the process of filming it? How long did it take and did you come up against many challenges?

Petr Lom: Yes, working in Iran was quite challenging, naturally, as there are almost no foreign film-makers there. I was very lucky to be able to work in Iran at all. And naturally, given the international political climate under Bush, the Iranians were very suspicious of any outsiders, and so I had to expend a great deal of energy trying to build trust.

theasiamag.com: Was there a fear of what would happen to those who spoke out against the government in your film, given that you were being watched?

Petr Lom : Naturally. But I chose to honour the courage of those who did speak out – I told them what the intentions and goals of my film were, and they chose to do so. Of course, many people also chose not to and did not want to be filmed. The fact that they do speak out does indicates that there is some variety of opinion in Iran. It is not a completely closed society, as, for example, Czechoslovakia was, when I was born.

theasiamag.com: Was there a moment in the film when you felt that there was a danger it would not have been made?

Petr Lom: Of course, most days. As I said, the Iranians are very suspicious of outsiders, and very suspicious of foreign journalists. There have been journalists who say they will make a positive film about Iran and then end up doing the opposite. So of course, the project was always precarious. I am happy and fortunate it worked out well.

theasiamag.com: How did you plan the story structure? Did you film with a story in mind that you wanted to tell? Did the film emerge the way you intended or did the story take shape as you went along?

Petr Lom: I proposed a film about the letters and Ahamdinejad’s populism right from the start of the project. However, I had a different film in mind. I had two goals that were not really achieved: (a) I wanted to make an observational cinema verité film about the president, which would have no criticism in it at all. I thought it would be far more valuable to make a film that shows how the leadership thinks and how it makes decisions. I thought this would be useful to understand Iran better. (b) I also hoped to get access to some of the letter writers and follow how their stories were processed and answered by the letter centre. But after many months of negotiating, this access was simply not given to me. So I had to assemble a film from the many different scraps that I had.

theasiamag.com: What are your personal sentiments with regards to Iran and its leadership? Did making the film change them?

Petr Lom: That is a complicated question. My main sentiment is this: Iran is a very important country. And it is a country that the West and the U.S., especially, must engage with. Not talking is idiotic diplomacy. I understand much better now, how crucial it is to treat Iran with dignity and respect, as an equal; and how the West must be extremely sensitive to symbolic politics – to a recognition of Iran and its dignity, and to be sensitive to its perceived historical ill treatment and colonial experience. Only in this way might there be a chance for greater peace in the region.

theasiamag.com: What do you want people to take away from it, after watching “Letters to the President”?

Petr Lom: To have greater sympathy for the Iranian people. I hope you will never forget the two ladies who complain about the price of strawberries.

Footnote: More information of the film is at www.letterstothepresidentmovie.com

Related Stories:

From Persia to the Islamic Republic

Israel through the eyes of Amos Gitai

Crossing the Muslim-Buddhist divide for love

Login or Register

Dan-Chyi Chua began her writing career with Channel News Asia, a regional cable network, before forsaking broadcast journalism to hit the road for a three-year sabbatical through the Middle East, China, Central America and Cuba. She has now grounded herself as a writer for asia! Magazine.

Dan-Chyi Chua began her writing career with Channel News Asia, a regional cable network, before forsaking broadcast journalism to hit the road for a three-year sabbatical through the Middle East, China, Central America and Cuba. She has now grounded herself as a writer for asia! Magazine.

- Asian Dynasties and History

- Conservation of the Environment

- Definition: Culture

- Economy and Economics

- Food and Recipe

- Geopolitics and Strategic Relations

- Health and Body

- Of Government and Politics

- Religion and Practices

- Social Injustices and Poverty Report

- Society, Class and Division

- Unrest, Conflicts and Wars

Another Point

Another Point An imaginary factual blog of General David Petraeus, Commander, United States Central Command

An imaginary factual blog of General David Petraeus, Commander, United States Central Command