BROWSE COUNTRIES/ TERRITORIES

Bhutan: Weaving a future

Nestled in the Himalayas, the Kingdom of Bhutan is one of the last unspoiled refuges of our time. It’s so beautiful, we are lulled into imagining it is God’s gift to tourists. The picturesque mountains and valleys are there to calm our senses; the ever-smiling people to populate our photographs.

But of course, if that is so, it is only incidental. For the Bhutanese, development, tourism included, carries its costs, too. It is the awareness of this downside that has led the Bhutanese king to make Gross National Happiness, as opposed to gross national product, as his government’s priority.

The aim is balanced growth— that is, to enable the Bhutanese to earn enough money to improve their lives, without having to sacrifice their traditions and beliefs to modernisation and mass tourism.

A closer look at the weaving industry illustrates some of the challenges of such an undertaking.

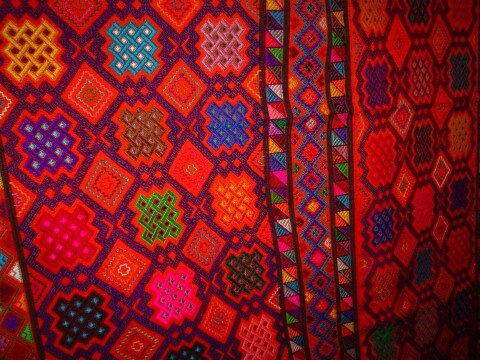

Bhutan’s traditional hand-woven products make wonderful souvenirs for visitors, representing as they do, the kingdom’s cultural traditions. And when marketed abroad to people who have yet to visit Bhutan, those shawls, wall-hangings, sofa-throws and fabric-lined briefcases become ambassadors of the kingdom, inviting some to make a visit one day.

Just as importantly, because weaving is largely a home-based activity, hand-weaves are a way of distributing tourism income to the common people. But bringing these indigenous handicrafts to external markets also involves a lot of hard work and hurdles to overcome. With more not yet overcome.

To begin with, weaving historically was for the family’s own needs and the local traditional market, said Joseph Lo, a Singapore working for the United Nations Development Program (UNDP), which supports Bhutan’s Rural Enterprise Development Programme (“RED”).

Weaving skills are quite widespread. Children—both boys and girls—as young as 12 to be taught to weave.

“Seventy per cent of households in the rural areas, especially the eastern part of the country, own a loom,” said Kinzang Tobgyal, a project manager in the Ministry of Trade and Industry.

Centuries of tradition preserved in colours

While this is a good starting point, the very local nature of the industry often means the designs are quite parochial too, at least before RED’s weaving project got underway. “The designs they had were difficult to market to non-traditional sectors such as for the tourist markets,” said Lo.

But how does one expect villagers in isolated valleys to be familiar with the tastes of the outside world? Clearly, some intermediating mechanisms had to be created.

The main point of contact with buyers is the Handicrafts Emporium in the country’s capital of Thimphu. Here, feedback is obtained as to what sells and what doesn’t. From there, weavers are motivated to innovate based on what they learn about customers’ preferences.

“But the weavers must first take ownership of the creative process,” said Lo. “If they don’t, they may keep producing the same designs or just wait for instructions, which goes against the essence of being an artisan.”

Thimphu is also quite far from the eastern-most parts of the country where the weaving activity is concentrated. There is only one paved road across Bhutan, and very little traffic.

“Thimphu is two days by car,” said Karma C Tsering, the Programme Co-ordinator for the RED Programme. “So the National Handloom Development Centre (NHDC) acts as the intermediary between the weavers and the markets in the West.”

“From the Centre, which is located in the eastern town of Trashigang, advisers go out to the field regularly” to disseminate information and know-how, she said.

Then there is the question of the limitations imposed by the looms themselves and the raw materials available.

The most popular type of loom is the “backstrap loom”, which, according to Jambay Zangmo of the NHDC, isn’t normally wider than 65 centimetres. It produces narrow strips of cloth that are sewn together into broader spreads of fabric. Hence the designs must be such that they can be joined. This complicates the production of broader articles such as bedspreads and wall-hangings.

Also, the Bhutanese traditionally derive their dyes from plants, which tend to produce relatively earthy or dusky tones. Bright yellows and luminous blues are out of the question. For these and other colours, the Bhutanese use synthetically pre-dyed yarn from India.

That’s a smart move because synthetic dyes need very careful handling so as not to pollute the environment. Bhutan hasn’t got the facilities to ensure that these dyes, when disposed, don’t leach into rivers. Not only its tourism industry, but its agriculture too, would be damaged by such pollution.

Nearly all of the cotton used by the weavers is also imported from India, which has a more suitable climate for growing the plant. Bhutan also sources its silk from India, but for religious reasons. The Bhutanese are devout Buddhists. Obtaining raw silk would involve killing the silkworm, and killing is a no-no in Buddhism. But importing these materials means a part of the profits also goes to India.

The next problem is scaling up. Villagers have very little money to buy raw materials. So, with seed funding from UNDP, NHDC set up a yarn bank in the town of Khaling.

From there “weavers with ID cards can obtain yarn on credit, with the payment deducted from the value of the finished goods that they hand in,” said Karma.

Marketing is another challenge. “We definitely need more awareness, more publicity and a unique branding,” Kinzang said.

He’s been working on e-marketing the products to the world, but notes that customers like to feel the actual product before they buy.

As for awareness, it becomes a matter of educating buyers on the difference between eco-friendly natural dyes and synthetic dyes; and how a typical 1.8-metre shawl takes a weaver eight days, working 10 hours a day, to produce. When people look at the product and the price, they ought to know what has gone into it, and not just compare it with machine-made items of synthetic yarn.

The lack of product innovation is also an issue. “While the weavers produced excellent products, there wasn’t enough range,” said Kinzang. “Thus we have come out with lifestyle products,” such as purses.

These products normally require sewing, so “ideally there should be supporting infrastructure,” he added, referring to factories. “That would add value as well as generate employment for increasing numbers of young people without meaningful work.”

But this would involve some industrialisation, which may change the character of the weaving industry. For example, factories may demand a regular supply of fabrics that weavers must deliver on time. Currently, weaving is a seasonal activity, subject to the rhythm of farming.

“The villagers see weaving as just supplementary income,” Kinzang said.

Does that mean that more Bhutanese need to become full-time weavers? Does that mean the community needs to start working to deadlines?

The danger, as in so many development projects around the world, lies in how, when upgrading an indigenous, supplementary handicraft activity to commercial scale, the joy and cultural meaning of the craft may be threatened.

Such are the dialogues between tradition and development, not forgetting that somewhere in between a path must be found towards Gross National Happiness.

Related Story:

Login or Register

Alex Au is a social and political commentator, gay activist and entrepreneur. He has his own website www.yawningbread.org

Alex Au is a social and political commentator, gay activist and entrepreneur. He has his own website www.yawningbread.org

- Asian Dynasties and History

- Conservation of the Environment

- Definition: Culture

- Economy and Economics

- Food and Recipe

- Geopolitics and Strategic Relations

- Health and Body

- Of Government and Politics

- Religion and Practices

- Social Injustices and Poverty Report

- Society, Class and Division

- Unrest, Conflicts and Wars

Another Point

Another Point From Jerusalem to the West Bank

From Jerusalem to the West Bank

Comments

Post new comment