BROWSE COUNTRIES/ TERRITORIES

Stealth, wealth and happiness

Worthy of a soap opera, the feud over Teddy Wang’s estate involved dangerous liaisons of all kinds.

For eight years Hong Kong-ers have been wondering how Wang Din-shin, an old man living on handouts, was able to wage a long and expensive lawsuit against Asia’s richest woman, Nina Wang, who is also his daughter-in-law.

Now they have the answer. If the gossip magazines are anything to go by, Wang Din-shin was being financed by a group of ‘investors’ who will pay for everything, from his upkeep and transport to the cost of hiring lawyers.

These people, a motley collection of property developers, casino owners, actors, songstresses, sports personalities and people with dubious mainland connections, had put HK$230 million($29.6 mil) into a war chest. The entire fund-raising exercise was conducted by two ‘organisers’, who each put HK$40 million into the kitty. Wang Din-shin had agreed to pay the investors a return of 20 times. In all, they expected to reap a windfall of more than HK$4 billion should Wang win his lawsuit.

Wang had been contesting his daughter-in-law for the control of the Chinachem group, Hong Kong’s biggest privately-held property concern. Chinachem was founded by Teddy Wang, son of Din-shin and Nina’s husband. Teddy, an astute but tight-fisted developer, was kidnapped twice, the second time in 1990, after which he was never seen again. In 1997

Din-shin asked the court to declare his son dead so he could begin the process of probate. (Nina, who was holding Teddy’s power of attorney, had been running the show). This led to an eight-year fight which only concluded this year.

Chinachem is valued at HK$40 billion. If Wang got his hands on the company, paying off his financiers would still leave him with HK$36 billion. This is not too bad for somebody who has been living on less than $10,000 a month, though it is difficult to see what a 94-year old man would do with all that money.

Does it sound a bit far-fetched? Not in Hong Kong. It is an open secret that many of the wealthy in the territory have engaged in activities that may not be entirely legal. During the Asian Financial Crisis in 1997/98, the sudden tightening of credit created a short but extremely lucrative opportunity for the cash-rich. It is said a textile tycoon made HK$200 million from lending his money at 20 per cent a month.

Lending money to someone for a lawsuit in

return for a share of the proceeds is a crime in Hong Kong. It falls under the act of champerty, a term that traces its roots to a Latin word that originally denoted the act of a feudal lord taking a cut of the harvest in his tenant’s field (see box below). Medieval lawmakers considered champerty a crime because they feared allowing profit-sharing in a lawsuit would help to exaggerate it.

This is certainly true for Wang Din-shin vs Nina Wang @ Kung Yu-sum, Hong Kong’s longest civil trial which stretched for 172 days and “devoured a significant part of our judicial capacity”, in the words of an appellant judge. It also cost the two sides more than HK$200 million.

The case came to its final conclusion on September 16, when the five judges of the Court of Final Appeal overturned two previous verdicts and ruled in Nina Wang’s favour. Nina, famous for sporting pigtails and wearing red vinyl miniskirts, had cut her hair and changed to more sombre clothing for the hearing. She is now the undisputed sole owner of Chinachem. A jubilant Nina, after celebrating with her staff, left for London. But her problems may not be entirely over. In January this year she was arrested and charged by police for forgery, the object in question is a will supposedly written by her husband in March 1990, a month before he was kidnapped. The Court of Final Appeal has found the will to be authentic. It now remains to be seen whether the police will drop the case.

Over at the camp of Wang Din-shin, it is all doom and gloom. Edward Chan, Wang’s lawyer, was shocked speechless when the verdict was announced. He then had the unpleasant task of calling Wang, who was not present, to tell him the bad news. Chan’s tribulations, however, were nothing compared with that of the two organisers who raised so much money for the lawsuit. They now have to deal with a bunch of angry investors who, as they are not able to resolve the matter through legal means, may take other measures.

Hong Kong is now abuzz over the identity of these investors. One person who is often mentioned, but who has shown himself to be not involved, is Albert Yeung, boss of the Emperor group, a hotel, casino and entertainment concern. Yeung was said to have been approached by the organisers to invest in Wang Din-shin, but refused the offer. Yeung, in fact, owed Nina Wang a favour. In 1994, when he desperately needed cashflow, Yeung was bailed out by Nina Wang who bought his building in Tsim Sha Tsui for HK$880 million. (The building is now renamed Chinachem Golden Plaza. In its front stands a statue of Nina Wang as ‘Little Sweetie’, her nickname by the media, with pigtails flying and bright short skirt blown up by a gust of invisible wind, ala Marilyn Monroe.)

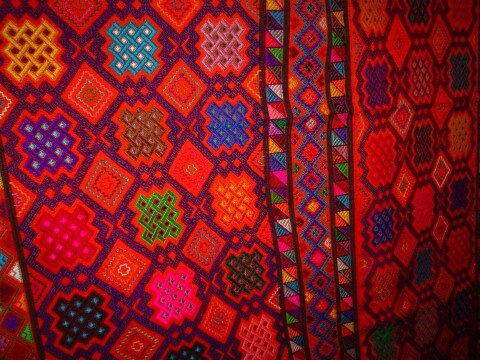

Teddy's widow, Nina Wang and her comic book character, Nina

In 2001, Nina, through an intermediary, asked Yeung to help persuade her father-in-law’s backers to settle. (She was said to offer HK$300 million while the other side demanded HK$2 billion, and neither side was willing to budge.)

Despite Yeung not being involved, many are still convinced he was helping Wang Din-shin. At the height of the trail at the end of 2001 and the beginning of 2002, posters with Yeung’s face, his name and the words “con man” appeared in many places in Hong Kong and Kowloon. Yeung was incensed. It was said his relationship with one or more of the ‘investors’ had never recovered from the incident.

Champerty and pasting libellous posters may be illegal, but they normally do not involve violence. On September 15, the eve of the verdict by the Court of Final Appeal, Kung Yan-sum, 62, Nina's brother, a practising doctor and a key witness, was attacked by four men when he was out walking his dog near his clinic in Sham Tseng. According to a police spokeswoman, Dr Kung was walking past a back alley when the men rushed out and hit him and the dog with wooden sticks. After a struggle and some loud yelling, the men fled. Dr Kung, injured slightly, was taken to hospital for treatment. His dog was badly hurt and was taken for treatment to a veterinarian at a nearby shopping centre. The police classified the matter as an assault, but it was also looking into whether the motive was kidnapping or robbery. Dr Kung, who sits on the board of many Chinachem companies, is said to be worth HK$600 million.

Having won the case, Nina Wang, when she returns from London, might decide to ask her father-in-law for costs. Wang Din-shin, through his lawyer, has passed the word that he has no intention of paying. “Take from Teddy’s estate!” he snapped. Certainly he can’t afford to pay. And it is no prize guessing what his investors will say if they are asked to foot the bill.

When getting a slice of the proceeds is illegal

Champerty is the crime of aiding another’s lawsuit in order to share in the gains.

The word may be unfamiliar, but champerty is a common practice in the US where it is known by another term: contingency fees. It is also called, unflatteringly, ambulance chasing.

For centuries, the English common law condemned champerty for fear the person practising it would be tempted to inflame a lawsuit for his own gain. Champerty, in today’s language, is a commission business: The bigger the lawsuit, the bigger the potential payout and the bigger the commission for the agent.

In recent years contingency fee agreements become not only permissible, but the norm, in the US, especially when it comes to the prosecution of speculative monetary claims.

Advocates of contingency fees say such arrangements also help those who can’t afford the rising cost of litigation to seek justice and compensation.

These pressures eventually led the UK to make conditional fee agreements – but not a percentage of proceeds – lawful in 1990. In Hong Kong, most forms of champerty are still considered illegal. In theory, therefore, if anyone has taken part in financing Wang Din-shin’s lawsuit against Nina Wang in the hope of a slice of the proceeds, he or she can be prosecuted. In practice, however, such cases are notoriously difficult to prove.

Related Stories:

Little Sweetie's fairytale life, with some bumps along the way

Nina Wang's will as provided by her family

Login or Register

Lee Han Shih is the founder, publisher and editor of asia! Magazine.

Lee Han Shih is the founder, publisher and editor of asia! Magazine.

- Asian Dynasties and History

- Conservation of the Environment

- Definition: Culture

- Economy and Economics

- Food and Recipe

- Geopolitics and Strategic Relations

- Health and Body

- Of Government and Politics

- Religion and Practices

- Social Injustices and Poverty Report

- Society, Class and Division

- Unrest, Conflicts and Wars

Another Point

Another Point An imaginary factual blog of General David Petraeus, Commander, United States Central Command

An imaginary factual blog of General David Petraeus, Commander, United States Central Command